| |

|

7Ss

of Business Growth 10+

|

|

|

|

|

The 7Ss of

exponential business growth 10+

are

Strategic intent,

Systemic innovation,

Synergies,

Simulation games,

Scaling

up, Speed, and

Sustained effort |

|

| |

Innovation is about love:

love what you do and love your

customers – both internal and

external ones.

Love the whole value creation

process if you want to truly

take care of all things and

succeed in

systemic innovation.

|

|

|

| |

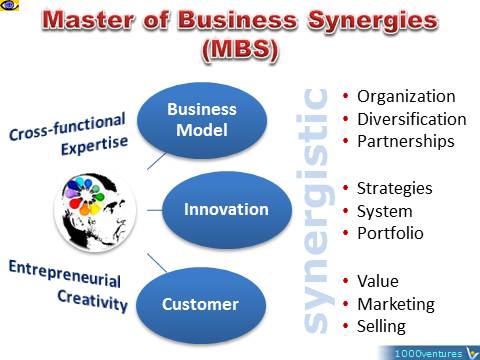

Synergy in business is the benefit derived

from combining two or more elements (or

businesses) so that the performance of the

combination is much higher than that of the sum

of the individual elements (or businesses). |

|

|

|

Synergistic Team

Synergy Innovation |

|

|

"Most teachings

about life, leadership, entrepreneurship,

business, strategy, and innovation work well in

life, but only until big challenges arise along

the way. In such cases,

super gamification comes to the rescue,

helping to successfully overcome big

challenges."

~

Vadim Kotelnikov |

|

|

If

you create something unseen

before, prepare to

address challenges

unmet earlier

~

Vadim

Kotelnikov |

|

Win first, them jump in.

Growth 10+ is a revolutionary

crusade that is to conquer many

diverse

enemies on on its way to

success. These enemies include

resistance to change, lack of

motivation and skills,

unpreparedness of stakeholders,

failures, and attacks of

competitors,

|

|

| |

Inspire your team members to

become

Impact Crusaders – missionary

innovators and change makers

whose energizing fire inside

burns much brighter than discouraging fires around them.

|

|

|

| |

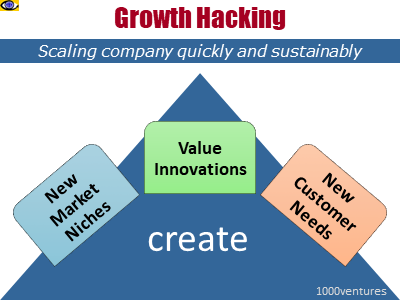

Scaling Up.

Scaling up means expanding or replicating an

innovative pilot or a small-scale project to boost and

broaden the effectiveness and impact of the innovation. |

|

Growth Hacking

Head of Growth |

|

|

|